Resilienta

Carolina Bazo is a Peruvian artist that has created a striking series of ecologically-charged videoperformances during the past five years. Both thematically and in terms of videography her videoperformances have put her at the forefront of video art in Peru, though she stands clearly at an angle to all other local artists working in new media. Without being an activist herself, she has elaborated potent visual constructs to cut through the barrier of human and non-human lives, and her work has become infused with an urgency that makes it an unusually bold plea for the living in the face of outright elimination.

Her approach has been to intuit how to bodily transcend the barrier between the human and a myriad forms of non-human presences in the rainforest, through fantastic imaginings that address the plight of life in the midst of deforestation and illegal mining for gold in the Amazon River basin in Peru.

Her videoperformances point especially to non-human forms of life, plant and animal alike, and she commits herself to bodily incarnating different beings through attire and enactment of rhythms, together with the suggestion of sensory responses of life forms to an environment that is alien to art audiences. In each videoperformance she studiedly proceeds to interweave a succession of instants into a choral structure. She plucks at the threads that make up the fabric of energy in the forest life-cycle, making an unconventional use of glitches or suddenly accelerating movement in the edit, by way of responding to the need of injecting visual vibrancy to the communication and dissemination of ecological causes, and succeeds in shifting the attention of viewers, unapologetically, to re-design what is really crucial to ecological concerns. Bazo confers a very different edge to representations, through the medium of video and the body as medium. She thus delivers visions from another planet that seems to be aeons away from the onlooker’s immediate context, reminding him or her of the persistence of a core of strangely seductive beauty.

Jorge Villacorta

--

Carolina Bazo es una artista peruana que, en los últimos cinco años, ha desarrollado una serie de videoperformances de gran impacto, marcadas por una profunda carga ecológica. Tanto en términos temáticos como en su lenguaje videográfico, su trabajo la ha posicionado en la vanguardia del videoarte en el Perú, si bien se sitúa en un ángulo particular respecto a otros artistas locales que exploran los nuevos medios. Sin asumirse como activista, Bazo ha construido potentes imágenes que atraviesan la frontera entre las vidas humanas y no humanas, dotando su obra de una urgencia inusual, que la convierte en un audaz alegato a favor de la vida frente a su sistemática aniquilación.

Su aproximación radica en intuir cómo trascender corporalmente la barrera entre lo humano y las múltiples formas de presencia no humana en la selva amazónica, mediante imaginarios fantásticos que enfrentan la fragilidad de la vida en medio de la deforestación y la minería ilegal de oro en la cuenca del Amazonas. Sus videoperformances señalan con particular énfasis las formas de vida no humanas, tanto vegetales como animales, y se compromete a encarnar corporalmente diversas entidades a través de vestuarios, gestualidades y la sugestión de respuestas sensoriales de los seres vivos a un entorno que resulta ajeno para el público del arte.

En cada videoperformance, Bazo articula un tejido coral de instantes interconectados, en los que desentraña las fibras energéticas que componen el ciclo vital del bosque. Su uso no convencional de interrupciones visuales, aceleraciones súbitas o distorsiones en la edición responde a la necesidad de inyectar vitalidad a la comunicación y diseminación de causas ecológicas, logrando desplazar la atención del espectador hacia una reconfiguración radical de lo que es realmente crucial en la crisis ambiental contemporánea.

A través del video y del cuerpo como medios expresivos, Bazo confiere un giro insólito a las representaciones tradicionales, generando visiones que parecen provenir de otro planeta, remoto y atemporal. En esta distancia, sin embargo, persiste un núcleo de extraña y seductora belleza que interpela al espectador, recordándole la urgencia de una mirada renovada sobre la vida y su inminente desaparición.

Selva Roja

Chaupiñamca

Lanzarota / Barna

Lanzarota

Barna

Dorotea

Peregrinaciones de una paria

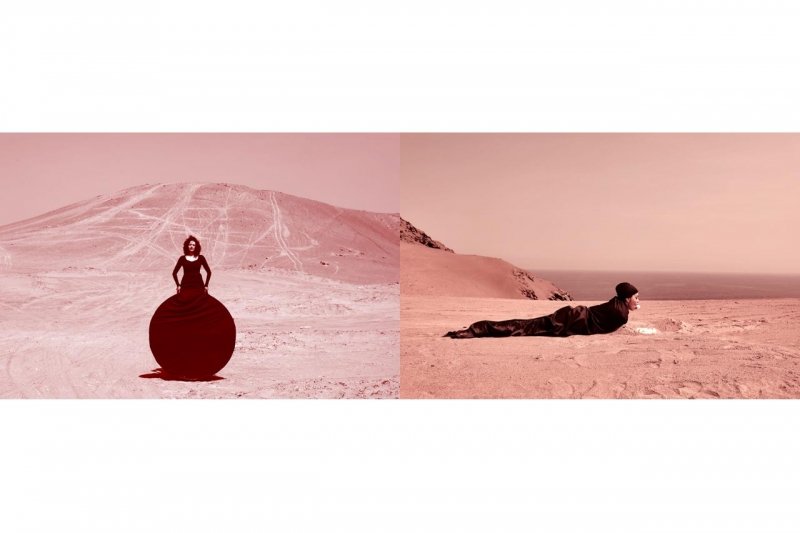

Carolina Bazo’s video works present us with enigmatic scenes that seem to come from a parallel world, like snippets of an eerie ritual devoid of any context. No narrative cue to these solitary actions taking place in nondescript locations is offered. What are we to make of them?

In the videos we see the artist quietly performing various simple tasks lik walking, crawling, standing still, etc., in places like the desert, a busy highway, the beach, the ocean. To the overall feeling of strangeness adds the fact that Bazo appears dressed in bizarre monochromatic clothes shaped like large geometric figures that partially conceal her body—costumes that recall the dehumanized silhouettes of the experimental ballets of early 20th century—. Even more disconcerting is seeing the artist nonchalantly popping eggs or spilling milk from her mouth in some of the works.

Bazo’s costumes are plain yet bold, and while in their weirdness they appear as cryptic as the minimal, almost expressionless gestures and movements of the artist, they offer us an interpretative hint to her work. Each costume involves a shape that in different ways narrows down the artist’s range of movements, without entirely determining them. Sometimes these shapes look like a burden to be carried (Pilgrimages of a Pariah), other times they come into view as a physical impediment (Patterns), as an appendage of the body (Mothers of the Desert), and even as an adaptive feature that enables certain actions (Patterns). In addition, there are elements that bring to mind maternity, like milk and eggs (Mothers of the Desert and Patterns, respectively).

It is thus that the artist simultaneously evokes and critiques societal mores, gender roles, and cultural habits, presenting them as something external (like so many outfits) that nevertheless models our behavior. Additionally, sometimes the costumes clearly stand out against their backdrop, while at others they blend with it, depending on their particular shapes and tonalities. The use of color inversions (Pilgrimages of a Pariah) further exploits the ambivalence of these figure/ground relations, which hint at the uncertainty we might experience before the vital crossroads we all face now and then. The span of choice that opens before us encompasses risk and possibility, as much as security and routine—something suggested by the use of recurring bodily movements and similar scenarios. Here repetition and constancy testify to the inexorable passing of time.

Carolina Bazo’s video works allude to the ways in which we negotiate with our environments, at times adapting to them, at others resisting them, even seeking to transform them or reinstate them. But perhaps, they are chiefly about endurance of a peculiar kind: one that is not just physical, but above all psychological, and emotional, and which is at the core of life itself: perseverance and preservation reaffirmed.

Max Hernández-Calvo

La Porfiada Roly-Poly

Mothers of the Desert

Patrones I

A character with her face covered by a red cloak and her body wrapped in a white blanket forming a peculiar geometric configuration, stands in the middle of a berm dividing a heavily traveled road; her dehumanized silhouette ripples in the wind. Her reckless quietness defies the street’s agitation and violence.

Another character, this time with her face uncovered, standing on the shore of the sea, evokes a sort of strange bishop or a surreal image of a nun. The character spits milk in a gesture with maternal, sexual and confrontational overtones, swims into the sea and disappears from our sight.

In this briefly described video-performance, Bazo’s characters are also abstract forms, symmetrical figures whose silhouette mark their actions. In a way, the forms themselves “perform.” Bazo alludes to sewing, design and behavioral patterns. Each form limits the possibilities of action: it limits or facilitates certain movements and responses to the environment. In that sense, rather than hiding, her costumes / disguises reveal the vital crossroads of these characters.

These silhouettes are repeated throughout the exhibition in a series of ceramic pieces (sculptures, plates and tiles) that exploit the background / figure relationships and the idea of repetition and difference—a constant in Bazo’s work. Many of the variations of these figures resemble human forms. In the ceramic plates decorated with these figures, some silhouettes are revealed to be visibly feminine. Framed in these utilitarian objects, an ornamental role in a domestic setting is suggested—one of so many patterns, roles, and places assigned in the social fabric.

Through design variations, the tiles invite a drift of formal associations, where the silhouettes can be read as references to: female bodies, body parts (noses, mouths, ears, vulvas, phalluses, etc.), accessories (pendants, medals, etc.), decorative objects (trophies, sculptures, ornaments) and household items (bottles, vases, candle holders). The idea of a pattern is doubly emphasized here: by the silhouette of the figure engraved on the tile and by the contour of the tile itself, which is highlighted in its relationship with the wall and with the other tiles. The whole installation constitutes a large inventory of forms that, in its own way, is also an alphabet of social and behavioral protocols.

The installation of ceramic sculptures works with these same silhouettes, which are cut and hinged in pairs in such a way that they become a three-dimensional element that breaks the figure / background dyad, “extracting” the figure from the background and turning it into an independent element. However, in the encounter between these cut-outs there are gaps and figures within figures—a sort of dialectic of presences and absences.

Arranged on iron pedestals, these figures resemble tailor mannequins, evoking the idea of models and by extension of a wardrobe—the silhouettes themselves evoke the costumes that appear in the video-performance. In that sense, Carolina Bazo suggests that our vestments are inseparable from our own (vital) performance and, although our costumes, roles and scenarios are familiar to us, they are no less disconcerting and less arbitrary than hers.