Patrones I

A character with her face covered by a red cloak and her body wrapped in a white blanket forming a peculiar geometric configuration, stands in the middle of a berm dividing a heavily traveled road; her dehumanized silhouette ripples in the wind. Her reckless quietness defies the street’s agitation and violence.

Another character, this time with her face uncovered, standing on the shore of the sea, evokes a sort of strange bishop or a surreal image of a nun. The character spits milk in a gesture with maternal, sexual and confrontational overtones, swims into the sea and disappears from our sight.

In this briefly described video-performance, Bazo’s characters are also abstract forms, symmetrical figures whose silhouette mark their actions. In a way, the forms themselves “perform.” Bazo alludes to sewing, design and behavioral patterns. Each form limits the possibilities of action: it limits or facilitates certain movements and responses to the environment. In that sense, rather than hiding, her costumes / disguises reveal the vital crossroads of these characters.

These silhouettes are repeated throughout the exhibition in a series of ceramic pieces (sculptures, plates and tiles) that exploit the background / figure relationships and the idea of repetition and difference—a constant in Bazo’s work. Many of the variations of these figures resemble human forms. In the ceramic plates decorated with these figures, some silhouettes are revealed to be visibly feminine. Framed in these utilitarian objects, an ornamental role in a domestic setting is suggested—one of so many patterns, roles, and places assigned in the social fabric.

Through design variations, the tiles invite a drift of formal associations, where the silhouettes can be read as references to: female bodies, body parts (noses, mouths, ears, vulvas, phalluses, etc.), accessories (pendants, medals, etc.), decorative objects (trophies, sculptures, ornaments) and household items (bottles, vases, candle holders). The idea of a

pattern is doubly emphasized here: by the silhouette of the figure engraved on the tile and by the contour of the tile itself, which is highlighted in its relationship with the wall and with the other tiles. The whole installation constitutes a large inventory of forms that, in its own way, is also an alphabet of social and behavioral protocols.

The installation of ceramic sculptures works with these same silhouettes, which are cut and hinged in pairs in such a way that they become a three-dimensional element that breaks the figure / background dyad, “extracting” the figure from the background and turning it into an independent element. However, in the encounter between these cut-outs there are gaps and figures within figures—a sort of dialectic of presences and absences.

Arranged on iron pedestals, these figures resemble tailor mannequins, evoking the idea of models and by extension of a wardrobe—the silhouettes themselves evoke the costumes that appear in the video-performance. In that sense, Carolina Bazo suggests that our vestments are inseparable from our own (vital) performance and, although our costumes, roles and scenarios are familiar to us, they are no less disconcerting and less arbitrary than hers.

Max Hernández Calvo

Rutilante

Carolina Bazo: The Void that Fills

Everyday life has a rhythm to it that fills as much as it empties our days with its routine.

In fact, the relay between “empty” and “full” is what configures a rhythm; sequence of mutually co-dependent presences and absences. Highlighting that an absence has as much presence as that that we call a “presence”, Carolina Bazo puts both terms in quotation marks in her “Rutilante” exhibition, suggesting that these poles are not just interchangeable, but oscillatory. And, perhaps, simultaneously one pole and the other.

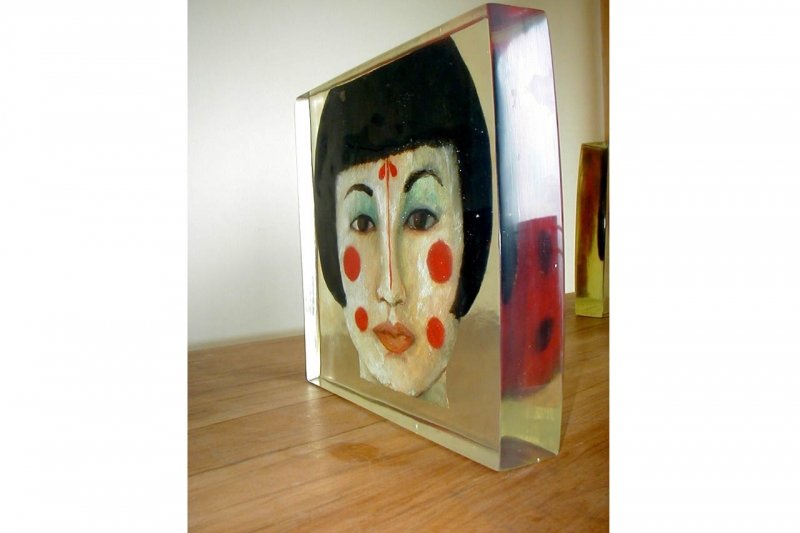

The artist’s basic unit is the conjoining of figure and background—it’s symbolic and aesthetic possibilities are explored in her images. Such individual images are threaded together in the work La colcha, which accordingly multiplies the unit’s possibilities in a tableau where non-discursive narratives interweave. But this figure/background tension does not only concern her paintings, for it runs through her works in resin, which tend towards icon-like imagery. And her icons are feminine.

That tension is emphasized by Bazo’s design patterns, which rule over certain works individually, as is the case with her “kaleidoscopes”—that series of circular works in resin, where the characters are arranged in templates of radial symmetry. But these patterns also organize large groups of works, as is the case with the 46 resin circumferences that make up the “Rutilante: revalorización del óvulo, medidas variables” series, the characters of which invite us to survey their similarities and differences as elements belonging to the set. In fact, the pattern is also transversal, given that “Rutilante” and “Caleidoscopio” repeat the same character that, in turn, extends the pattern through its details. These characters wear a “corset” (which emphasizes their curves; stereotypical sign of femininity) made up of dots that internally—and on a small scale—replicate the circularity of the format. This replication is also nominal: “Rutilante” within “Rutilante”.

In these series, the compositional structure is a pattern of visual repetition that evokes routine as a pattern of lived repetition. The reference to the ovule and its cyclical pattern of biological change for women isn’t fortuitous. Repetition and change, perceptible and imperceptible (somatic or psychic). In that sense, the resin pieces do not only explore the ambivalent correlation between figure and ground, but they equally touch upon the contours of space and time as a gendered experience.

In two dimensions, the figure-as-silhouette stresses the “feminine shape” that the monochromatic backgrounds emphasize. In three dimensions, the transparent resin backgrounds stand up as the materialization of empty space: a tangible “neutral shape” in itself. The reification of this “void” annuls it as such and, nonetheless, it somehow preserves its illusion: its “coloured transparency” allows perceiving it as the “surrounding space” of an image-silhouette and/or of an object. At the same time, actual empty-space becomes displaced, surrounding resin’s “solidified space”, underscoring the homogenizing ubiquity of space. After all, everything and everyone is “trapped” in it.

The idea of time-flows traverses the works where the artist has trapped, amber-like, various objects of quotidian use, as if they were fossils of everyday life. In the portrait series, “Equilibrio”, which bear a certain resemblance to religious icons, Bazo arranges an almost mystic relation between characters and objects. Those (mass produced) objects reveal themselves as fetishes of the everyday, which we accumulate in our homes and with which we occupy our lives, almost to the point of saturation. But this is a saturation that ornaments. The objects even appeal to vanity, where their saturated colour enables their use as “accessories”. This reiteration of objects and images links vanity and saturation: ¿is it about the artist’s own saturation, whose characters do not shy away from self-portraiture?

In these resin pieces, time has been stopped and extended: the objects seem preserved in “suspended animation”. And their accumulation—constituting a peculiar archive—implies in and of itself the passage of time. But, also, by “floating” without ever falling to the ground, they evoke a frozen instant. Such instant can be linked to a film still, as intimated by the cuts of the “triptych” El cuerpo se divide en tres partes (the body is divided in three parts), a title that brings to mind those old litanies: “head, torso, limbs” and “mind, body, soul”.

The characters with their eyes closed—asleep?—doubly float: submerged in resin and in the dream world. They remain outside everyday routines yet allude to the practical world embodied in the objects (do they dream of this world?). They’re isolated from the world yet escort societal aesthetic codes of seduction (make-up, accessories, lingerie). They’re as if disconnected from life yet they intimate biological routines, such as sleeping (or ovulating). Bazo’s enclosed characters are in a sort of limbo: busy and occupation-free, saturated and empty, free and trapped.

The artist suggests in “Rutilante” that the opposing forces that fill and empty life are in affective rather than material equilibrium. On one hand, there’s the gravity of her compositional order, her serial repetition and her allusions to routine as a pattern that is traced on our very lives. On the other hand, there’s the playful character of her images, the reminiscences of childhood channelled through her objects, and the sensuous range that her colour and shapes put forward.

In other words, what Bazo engages is the emotional ambivalence that we place ourselves in the world with, and from which we determine its meaning. Full and empty are affectively determined categories: a silence can be a full reply just as a discourse can be affectively equal to silence to someone awaiting a truth. In the end, Carolina Bazo’s “Rutilante” allegorizes the sort of abyss in which we inevitably float, as if sleeping, as if playing, as if living.

Max Hernández Calvo, February 2011

Escensia doméstica

Seduction starts within the package. Desire arouses along the proliferation of shapes and sizes. Everything has a purpose; shape, size and color. Producers play safe with standard, uniform and duplicable layouts. Industrial design finds its meaning not only by relying on pleasant and decorative patterns, but also by creating memorable images. Consumers feel really well as long as they have the conviction that someone shares their sensibility and preferences. A scent is a perfect abstraction for flattering one’s senses to the point of believing a vanishing fragrance has been personally and naturally created for one. It so happens that consumers don’t realize that as production grows, the bogus illusion of individuality is doomed to fade away. But this is just a part of a big scenario that has led Carolina Bazo’s research as she imagined a non standard line of artistic products based upon an altered matrix of a designers perfume.

Because asymmetry expresses the appeal of an artificially not mass-produced object, Bazo’s line is meandering and irregular. Each case depicts an individualized design proposed to please every social imaginary consumer’s sensibility, no matter the sex nor the age. Everyone will discover that the organic and abstract shapes represented on the resin plates are actually little faces, real identities. The artist plays subtly with this female depictions: a spider-woman, a chubby midwife, a femme fatale, a joyful old woman, a rebel teenager, amongst others. These also refer to a symbolic exchange, where no one is led towards a romanticized perception of human nature as an eternal asset. Encapsulated form and color could be a powerful suggestion that feminine beauty is a precious commodity. The lack of unity and uniqueness points out, however, that formal beauty is not a viable option. There is no need to rush to say that beauty equals eternal value, just as it is not provable nor eternal -woman’s essence- the so called Eternal Feminine. By means of this materially devoid installation that insinuates, speculates, disenchants, distills and breathes a plural femininity, it is asserted that individuals still need to fully recognize themselves in others to affirm togetherness in a world that is contingently, contentiously and belligerently changing.

Jorge Villacorta

November, 2009

Lavandediario

Vivimos en un mundo aséptico y ordenado. Un entorno que se opone diametralmente a un mundo natural, caótico y sucio. Para Carolina Bazo lo sucio está representado por aquello que «mancha»; todo lo que está donde no debería estar, aquello que no pertenece a nuestra aséptica realidad cotidiana. El jabón de resina contiene la síntesis de una paradoja material: aquello que supuestamente debe limpiar es también un agente tóxico de contaminación y muerte. La asepsia del mundo moderno supone la destrucción del mundo natural. El personaje representado en los jabones —los de color carne funcionan como una alegoría del cuerpo, y cuya reproducción en serie evoca la repetición mecanizada de la vida diaria— sugiere una mujer pulcra y diligente literalmente atrapada en un bloque de resina, que al mismo tiempo actúa como refugio y celda, protegida y aislada del mundo exterior natural y sucio.

La rutina es un tema recurrente en la obra de Bazo. Los horarios repetitivos y la constante lucha contra el tedio de vivir en un universo domesticado y predecible han generado un escenario donde el dibujo, cuyo significado queda suspendido, surge como la manifestación de lo indeterminado. Siguiendo la lógica del automatismo, los dibujos nacen espontáneamente (como aquellos garabatos que hacemos sin darnos cuenta mientras estamos inmersos en otras actividades) y aparecen sobre corrientes mayólicas industriales ―con la misma clandestinidad del graffiti. Los dibujos irrumpen en la existencia seriada de cada loza para darle un carácter único, arrancándola de su anonimato, y logrando con ello una pequeña victoria estética sobre la racionalidad del mundo organizado: la irreductibilidad y autonomía de la imagen sobre la narración.

La disposición de las mayólicas transforma el espacio de la galería en una lavandería, donde todos sus ocupantes (personas y objetos) son lavados diariamente atrapados en el obsesivo ritual de limpieza de la vida moderna. En Lavandediario la pulcritud de la vida ordenada es ensuciada por la ocurrencia de un impulso vital que, discordante e indomable, se niega a formar parte del simulacro, rescatando en su emergencia la gratuidad del arte y la vida.

George Clarke

Lima, septiembre, 2014

Ascendencia

Angela Davis

Vestuario

Distracción y dislexia definen los puntos de partida de "Vestuario". Éstos trascienden a la anécdota personal y se presumen constituidos como pauta para la creación de las imágenes presentes, dada la particular atención y percepción que la obra de Carolina Bazo nos solicita.

Esta muestra recorre dos aproximaciones expuestas en dos grupos de trabajos. Por una parte, imágenes' suspendidas en resina (una pieza bifronte un personaje múltiple, por llamarlo de algún modo y una serie de retratos) en las que la transparencia y la traslucidez y el orden cuadricular en el que están dispuestas son fundamentales. Por otra, cuadros (retratos, escenas de situaciones bizarras) cuyas composiciones se organizan de acuerdo a patrones no-ortogonales y aparentemente aleatorios. Más allá de las diferencias, el conjunto de obras apela a un juego de confusiones ópticas, donde fondo y figura tramitan su preeminencia en nuestra retina. Por medio de tal juego Bazo insinúa las complejas relaciones entre individuo y colectividad, que, en sus organizaciones más rígidas (en las cuadrículas, por ejemplo), sugiere una necesidad de diferenciación llevada al punto de la indiferencia. Así, enfatizando la vestimenta-como-piel, "Vestuario" atiende a la noción de encubrimiento, que sus personajes revelan por medio del disfraz (las máscaras son su cara visible).

Este encubrimiento también se expone en la piel revestida. Conceptual e iconográficamente (como en la descripción cosmética de sus personajes), el maquillaje es tópico y referente en las imágenes de la artista como la cubierta con la que muchas veces enfrentamos al mundo para, irónicamente, no-enfrentarlo. La noción de maquillaje parece incluso desprenderse del tratamiento de superficie de sus cuadros, que refuerzan técnicamente la sensación de artificialidad a la que alude; la obra misma parece encamar en su factura tal condición. Se diría que la piel-del-cuadro ha sido acicalada por la artista. Y acaso sea porque la duplicidad es una preocupación base. entendida como un mecanismo que empleamos para salimos con la nuestra, si bien siempre enmascarando, compensando e inventando la situación: maquillándola (making it up?).

La extensión del juego visual que "Vestuario" pone en marcha se hace patente en los patrones de diseño como una constante. Aquí la lógica de la dislexia impregna el registro de lo visual en las inversiones de figuras y las trasmutaciones de fondo y forma. Las figuras que construyen patrones abstractos, formas de inspiración orgánica, coquetean por momentos con un orden fractal en su gradación. La atención cambiante que figura y fondo solicitan, se despliega imaginariamente como una distracción al-punto-de-la-ensoñación, en un recorrido del patrón abstracto al icono figurativo (caracoles, cerebros, peinados, etc.).

Acaso en sus distintos recursos visuales Bazo ronda el camuflaje (en la repetición de formas, de patrones, de iconos) y acoge la mímica como un modelo de construcción estética, pero también de comentario crítico. En tal medida, la obra misma parece parodiar la misma lógica que pretende exponer, una lógica de comportamiento ligada a las tensiones y confusiones entre individuo y masa; más aún, a las desapariciones de la individualidad en lo masivo (y sus desesperaciones por lo masivo) de ahí sus guiños a la moda y su appea/por el maquillaje.

Las inquietudes por nuestra cultura de repeticiones y reproducciones sistemáticas y sistematizadas clonaciones estéticas y comporta mentales incluso quedan seductora mente expuestas en un trabajo que en su modo de construcción misma, y nominalmente incluso, evidencia aquello que temática e iconográficamente aborda. Duplicidad, con todo, pero como una irónica repetición final, como si de una risa última (y mejor) se tratase.

Max Hernández Calvo

Lima 2004

Fósiles actuales

Collar Global

The solidified transparency of Carolina Bazo’s resin pieces highlights the operation of framing and the mode it establishes visual hierarchies by singling out an element. But such hierarchy is countered by repetition, as in the prints. Here the necklace is an emblem of repetition (one bead after the other), echoed by the female figures wearing them, whose variations in skin colour only stress the serial nature of their icon-like character. Their background presents yet another pattern, with shapes quite similar to those of the necklace. However, the dramatic contrast between the various patterns at play (abstract shapes, female silhouettes, facial features, necklaces, etc.) creates a “struggle” for the foreground, to which each element seems to lay claim. What counts as an accessory here, where the very configuration of the prints furthers the visual relay between the different parts? What part plays a secondary part here? What we have is a whole made out of parts which resist adding up, defying their manifest correlation.

La transparencia solidificada de las piezas de resina de Carolina Bazo resalta la operación de enmarcado y el modo en que establece jerarquías visuales destacando a un elemento. Pero tal jerarquía es contrarrestada por la repetición, por ejemplo, en los grabados. Aquí, el collar es un símbolo de repetición (una cuenta después de otra), cuyo eco resuena en las figuras femeninas que los usan, cuyas variaciones de color de piel sólo insisten en la naturaleza seriada de su carácter icónico. Su fondo presenta otro patrón más, con formas muy similares a las del collar. Sin embargo, el dramático contraste entre los diversos patrones en juego (formas abstractas, siluetas femeninas, rasgos faciales, collares, etc.) crea una “lucha” por el primer plano que cada elemento parece reclamar como propio. ¿Qué se considera un accesorio aquí, donde la propia configuración de los grabados fomenta la conmutación visual entre las diferentes partes? ¿Qué parte juega un rol secundario aquí? Lo que tenemos es un todo cuyas partes se resisten a sumarse, desafiando su correlación manifiesta.

Max Hernandez

Retratos

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference. Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

Tal vez si damos cuenta al reloj ya dio la hora vacía. Y es en esa hora, que Carolina Bazo llama así, en la que se ubican sus personajes, mas bien en la que se quedan, casi como atrapados. Los retratos que ella nos ofrece (Que recuerdan un poco a una foto carné, pero también a una estampita) están capturados en resina, puestos en un espacio no sujeto al tiempo, como ocurren con aquellas criaturas que el ámbar preserva eternamente en el aislamiento. Estos personajes fuera del tiempo son en cuanto a individuos- inmutablemente diferentes. Estas piezas incorporan, junto con la imagen del sujeto, un objeto particular que lo define que lo identifica. Como si de un atributo se tratase, el objeto corresponde a ciertas características del retratado, en este caso encarnadas en la vestimenta, pero también en un adorno, en un detalle: la persona y su característica hechos uno.

Estas imágenes son bifrontes y como tales incluyen información que el referente fotográfico aludido -la foto carné- excluye. Esta estrategia junto con la de los objetos/atribuidos que incorpora en las resinas forma parte de un particular acercamiento al retrato que lleva a cabo Carolina Bazo y que involucra representar al sujeto en la abundancia de al imagen para ser algo mas que mera imagen: un individuo. Pero también un objeto.

Estos grabados evidencian una carga más bien psicológica, en donde el entorno y la interacción son los elementos claves del trabajo. En estas piezas por medio del característico dibujo de Bazo se construyen escenas en las que algún tipo de narración reflexiva sobre lo familiar y lo cotidiano destaca, aun si ésta es sutil en el humor que predomina en ellas.

Max Hernández Calvo

Mayo 2001